Do You Have High Blood Pressure—or Badly Measured Blood Pressure?

Overdiagnosis is the medical version of a felony on your record—putting you at risk of overtreatment by every doctor you see

Needing to pee is a condition we treat with directions to a toilet.

Needing to pee while getting your blood pressure taken can get you treated with a BP-lowering drug you don’t need—causing cascading harms to your health.

Say your actual resting blood pressure is 115/70.

That’s normal blood pressure—blood circulating at a healthy rate of speed.

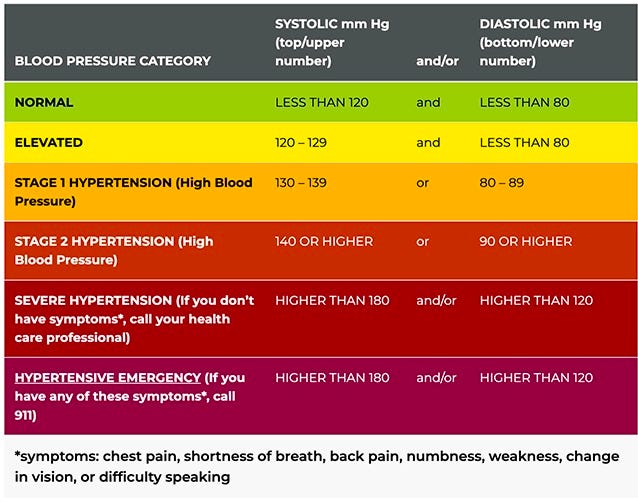

The urge to pee can spike that number by 15 on top and 10 on the bottom—bringing it to 130/80—Stage 1 high blood pressure.

Which you don’t happen to have.

Correct diagnosis: Three Diet Cokes during a crazy-busy morning and no time to run to the john.

Reason to “work smarter,” but not an actual medical condition.

BP Measurement Fails

Reading papers on blood pressure, I realized I have never had my blood pressure taken correctly.

The needing-to-pee problem is just one of many factors that can artificially inflate a blood pressure measurement.

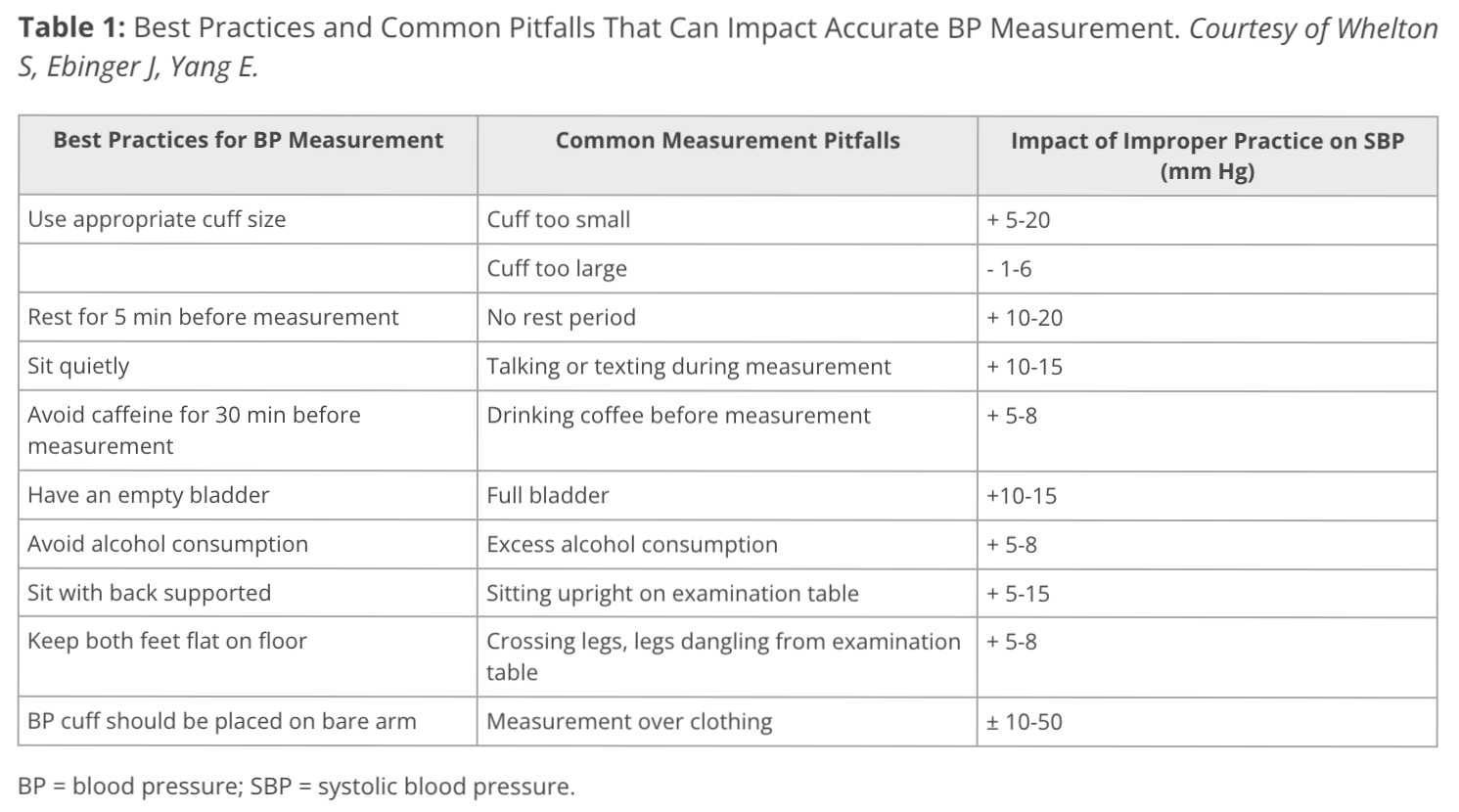

Cardiologist Seamus Whelton, MD, and his colleagues created this chart showing common ways (systolic) blood pressure measurement becomes blood pressure mismeasurement.

It’s not a complete list. Other BP measurement pitfalls include:

OTC PAIN MEDS: Ibuprofen and acetaminophen boost BP by 3.7 and 4.7 points respectively.

IGLOO-ESQUE EXAM ROOMS: Cold causes blood vessels to constrict—a heat conservation measure—elevating BP by varying amounts, greatest in older people and those with high BP.

THIRST: Being thirsty is a sign of inadequate fluid levels in the body. Blood vessels constrict to adapt to the lowered levels. The slimmer the pipes, the harder your heart has to work to pump the blood around, raising BP by varying amounts.

All of These Wrong Numbers Can Really Add Up

Why High BP Matters

Blood pressure is the force it takes to circulate blood around our body—measured via the blood rush hitting the walls of our arteries.

Actual high blood pressure—“hypertension,” accurately measured—is a nefarious thing. So many disorders do us the courtesy of a prompt heads up, like with the medical yoohoo of projectile vomiting, elephantine swelling, disemboweling pain.

Not high BP.

It hides inside our arteries, furtively doing its nasty work: weakening and stiffening them and causing abrasions in the smooth lining, which allow fats and cholesterol to infiltrate and then narrow our arteries with plaque.

For years or even decades, high blood pressure is imperceptibly ruinous—until that eventual 911 moment: dropping us with a stroke or heart attack or revealing an acute need for an aftermarket kidney.

This makes it vital to regularly measure our blood pressure and address any departures from “normal” levels pronto; ideally, with lifestyle measures rather than drugs. (Covered in the upcoming Part II of this BP series.)

Getting “Healed” To Death

Your doctor’s care should not lead to a hip fracture or your head being smashed on the pavement like a pumpkin.

But that’s exactly what can happen if, due to measurement errors, you’re put on BP-lowering meds you don’t need—giving you a medication-induced disorder you did not previously have: low blood pressure, potentially in the range of 90/60—or lower.

This can sock you with:

• “Orthostatic hypotension” (aka the pumpkin-meets-pavement problem)—going woozy when standing up and maybe even blacking out and dropping like a rock. (This is a major cause of hip fractures in older patients.)

• Fatigue and brain fog. Beta blockers—drugs like propranolol, with an “olol” ending—are big perps here, reducing blood and oxygen transport to the brain and blocking norepinephrine and normal alertness.

• Messed-up kidney function. Diuretics and meds called ACE inhibitors screw with water and salt handling. This can stress the kidneys and cause electrolyte imbalances from low sodium and/or potassium.

• Polypharmacy. This only sounds like a drug-fueled orgy. It is drug-fueled. It’s a pharmaceutical pile-on—the term for being prescribed five or more meds you take regularly, often leading to even more meds to mitigate the adverse effects of the first pack.

How likely are you to be prescribed BP drugs you don’t actually need?

Well, under the revised 2017 BP guidelines, 65-72% of people whose systolic BP is 120-129 will be wrongly diagnosed—overdiagnosed with “hypertension”—report epidemiologist Katy Bell and her colleagues.

Help Yourself to a Correct BP Reading

PARTNER WITH THE PRACTITIONER: Let the nurse or other practitioner taking the reading know it’s important to you to get your blood pressure number right—and you want to work with them to do that.

SIT LIKE A KING: Back supported and both feet on the floor.

GIVE YOUR ARM A REST: Your arm should not be hanging down by your side like an orangutan but supported on a flat surface.

That surface needs to be high enough so your upper arm (and specifically, the cuff) is at heart level, just like AI-generated Annie here.

Accept no too-low substitutes. Ask for a small table to be moved into the BP-taking room.

BP CUFF SHOULD FLIRT WITH YOUR ELBOW: The bottom of the BP cuff goes just above the bend of the elbow.

MEDITATIVE, NOT MANIC: “Rest for 5 min before measurement” from the Whelton chart means “sit quietly for 5 minutes before a reading is taken,” with your arm all prepped and ready on that flat surface, like AI Annie’s.

To make this a medical reality, ask the nurse to give you five minutes so you can calm yourself enough to give them a correct reading.

Your phone? Silenced, face-down, and across the room, you doomscrolling junkie.

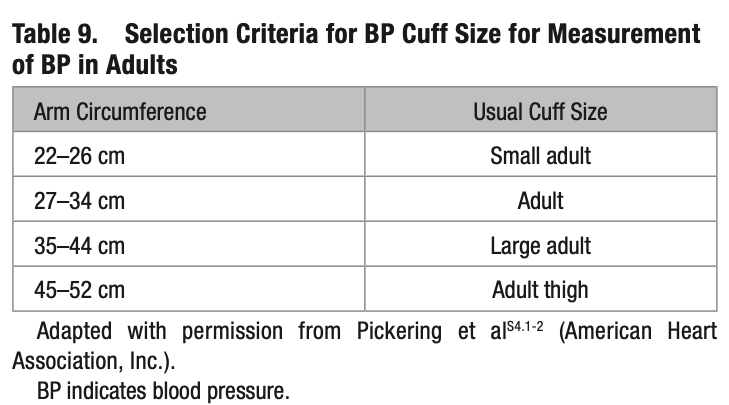

KNOW YOUR CUFF SIZE: If you’re a big fella, you need the husky-sized cuff.

Figure out your size before you go to the doctor, lest Nurse Nellie try to fit you with Barbie’s BP cuff.

Helpfully, the Whelton team included this size chart, with the size names in the right column—though “Adult thigh” is actually the size for “Extra-large adult.” (More on sizing at the bottom of the post.)

A Single BP Measurement is Not Enough

In blood pressure measurement, “one” is not only “the loneliest number,” but the most inaccurate, because the initial BP reading tends to be overly high.

A possible perp—right out of the medical literature? “White coat syndrome”—being freaked out at getting your blood pressure taken (due to what that could mean for your health) or just being at the doctor’s office.

Or, if you’re like me, it’s the breathless race to your appointment as the clock is about to strike like a reproachful guillotine.

Immediately following your first BP measurement, ask for a second. No need to wait three to five minutes, as has been the practice; the second reading can be taken a minute after the first. (Ideally, there would also be a third.)

If your first reading’s high, it might seem you’d stay “all het up” for the second. In fact, cardiology specialist Matthew Alexander finds that a second measurement leads to a “lower averaged BP,” better accuracy, and, the biggie: “improved cardiovascular risk prediction.”

Don’t Let Mismeasurements Become Medical Records

Whenever a BP reading is high relative to my usual blood pressure, I ask the nurse to throw it out and do a retake—noting that I have a verified medical BP measurement device at home and my normal BP is 99/62.

You don’t need a device to make the case for a retake. You could just tell the truth: “That reading seems wrong.”

That might work. But your best bet is blaming “white coat syndrome.”

It seems to bypass a nurse’s “Well, hellooo, medical princess!” defense system—probably because hearing medical jargon they recognize triggers reward circuits in the brain, both out of familiarity and professional validation: a reflection of their medical knowledge and competence.

If they bristle, persist. And remember that you have two jobs on the BP agenda:

Get a redo (or two if you can).

Insist the first reading (or any other elevated readings) be excluded, lest they be averaged in, falsely elevating the total.

Keeping that el-spike-o first number out of your chart is vital.

And not just because it’s wrong.

How a Medical Record is Like a Criminal Record

For a responsible medical practitioner, a single lab value or test number is a data point to investigate further, not a diagnosis. And then there are irresponsible practitioners. They’ll glance at a single BP test and write “Hypertension” into the “Ongoing Conditions” part of your chart—which gets you deemed diseased.

Sure, you could show evidence the number is wrong or work to bring down elevated BP to a healthy level, but what goes into your chart tends to be very hard to get removed. At best, it shape-shifts slightly.

As epidemiologist Katy Bell and her colleagues put it in the Journal of Hypertension:

Once a person is diagnosed with ‘hypertension’, they do not later become undiagnosed as a result of lower BP measurements, but rather they are said to have ‘controlled hypertension.’

This “diseased on paper” thing warps the perception of doctors who read your chart—and how they diagnose and treat you. You can explain that it’s wrong, a testing error, but doctors, medical administrators, and other medical employees tend to have a quality bias—assuming that their colleagues who’ve diagnosed you were rigorous and right.

This can lead to your getting denied drugs you need, pressured to take drugs you don’t, or coerced to get unnecessary tests that sock you with radiation or otherwise put you at risk.

You Have a Right to Medical Accuracy—and It Starts With You

The best defense against being mistakenly declared some sort of geyser of blood pressure is a body of evidence: a slew of BP readings that say otherwise.

I strongly suggest you measure your BP at home—as do all the major cardiovascular medical organizations.

Blood pressure fluctuates throughout the day. Self-measurement gives you a real-world picture of your blood pressure IRL, in your “natural habitat”—as opposed to the temporary artificial environment of your doctor’s office (the equivalent of a medical zoo).

For those who aren’t up for buying a device, you can do home measurement with a medical device your provider loans you for a day. Ask your doctor for ABPM, Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring: a 24-hour detailed BP measurement.

You’ll get a BP cuff attached to a small recording device that takes readings of your blood pressure and heart rate every 20 to 30 minutes during the day and every 30 to 60 minutes at night.

ABPM beats doctor’s office BP measurement for accuracy and provides all sorts of detail the office version does not, like whether you have healthy “dipping” during sleep (10-20%).

But because ABPM is just a 24-hour snapshot, it lacks the benefits of daily or regular self-measurement. There are three biggies:

A collection of BP readings is a powerful counterpoint: discrediting the here-and-there inaccurate measurements at your doctor’s office.

You’ll see patterns—changes throughout your day and from month to month in your BP metrics during, say, exercise or sleep.

The numbers will tell you whether you might need to make some BP-reducing changes—and, if so, with continuing measurements, you can see the results.

(In the next post in this series, I’ll cover how to prevent and/or lower high BP—along with exposing the medical underthink driving current diagnose and treatment.)

How to Buy and Use a BP Measurement Device—and Log Your Measurements

THE DEVICE: For correct BP measurement results—and credibility with your doctor—use the American Medical Association’s ValidateBP.org site to buy a device that meets their standards for accuracy. The dabl Educational Trust has another list of validated devices.

As an alternative, you can do as my primary care doctor had me do with my Homedics device—bring it in and have a nurse test my BP on their medical-grade device and compare the results. (They were just a hair apart.)

THE CUFF: Upper arm cuffs, not wrist cuffs, are recommended. Get sizing help under the Resources pulldown at the top of ValidateBP.org.

THE “HOW-TO”: Detailed guidance on how to take your BP under the Resources pulldown at ValidateBP.org.

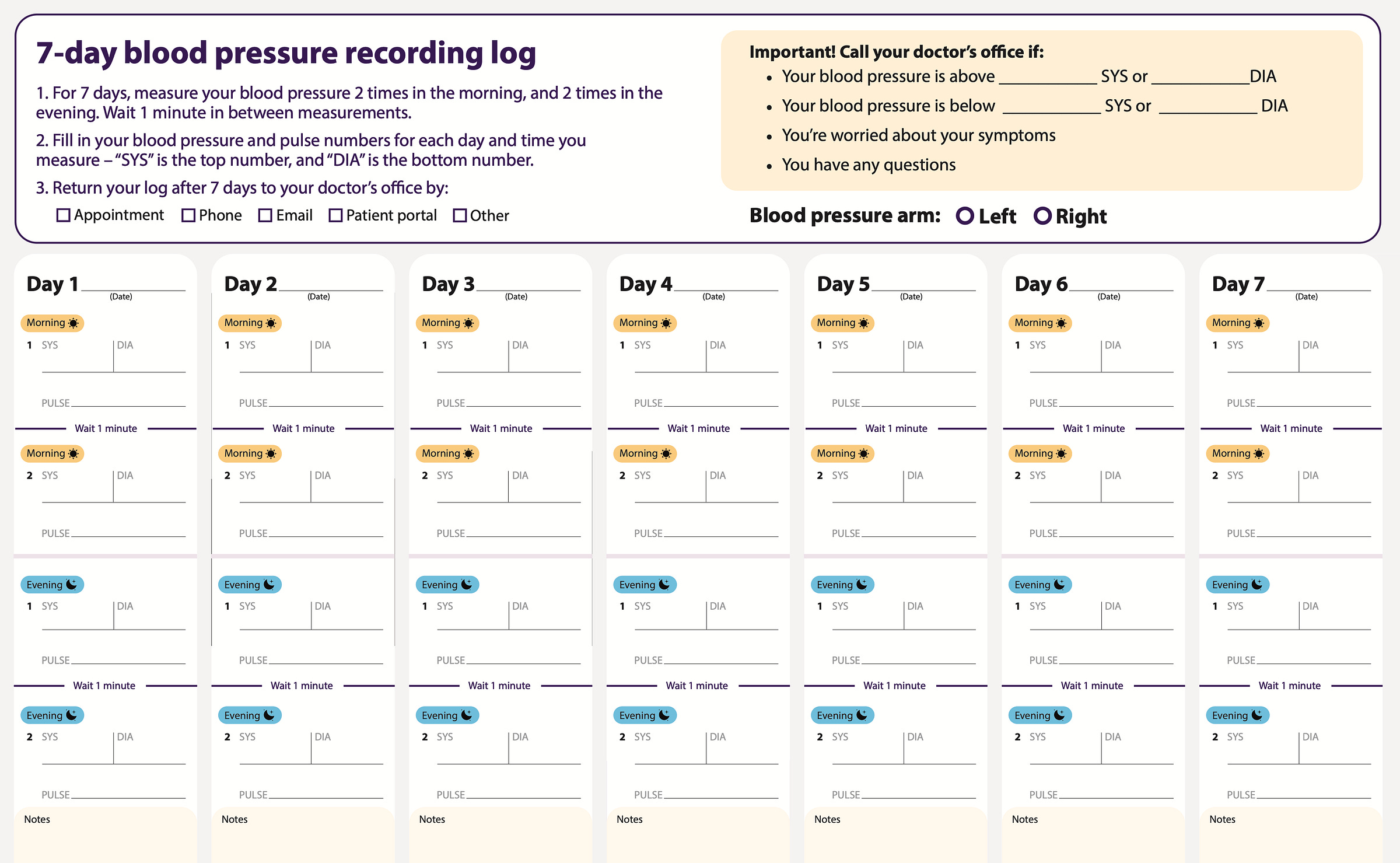

LOG IT: There’s even a handy log to download (see below), though many people will just take a photo of their BP monitor with their phone each time. That’s what I did.

But a combo approach is probably best: photo verification of at least one BP reading a day, plus filling out this chart to give your doctor the big picture.

CONSISTENCY: Take your BP at the same time and under the same circumstances each day.

And a request: In the comments, let me know how it goes—or how it’s gone: your experience with BP measurement and mismeasurement. And feel free to post any questions you want me to take on in future posts or the comments!

Finally, if you like my posts—which I put a lot into—please throw me a like below. Helps!

NEXT: Coming Up in Part II of this BP series:

Numbering Us Sick: High Blood Pressure Is The Wrong Problem

It’s a sign, not a diagnosis.

Doctors fixate on bringing down BP numbers with drugs—often to the detriment of patient health in those with milder levels of hypertension—while failing to lower the risks of heart attack, stroke, or premature death in these patients.

Though it’s not always possible to know the cause of high BP, even when we don’t, we can take steps to fix it—in doable, lifelong ways.

Which I lay out for you in this upcoming post!

Help Me Help You! (Please Donate.)

I need your financial support for SCIENCE MADE PRACTICAL to continue my 30-year mission of putting out rigorous, highly practical applied science.

You’ll be helping fund my deep dives into research across disciplines and the doable applied science solutions I come up with for you and all my readers.

Ways to Donate:

• PayPal (one-time—or monthly or yearly donation)

• Credit or debit card (one-time donation)

• To use another method, please email: info@amyalkon.net

Buy GOING MENOPOSTAL:

What you (and your doctor) need to know about the real science of menopause and perimenopause

“This is a rigorous and meticulous guide to everything related to menopause. … Alkon does a tremendous job of breaking down scientific facts for everyday readers. … Her smart, thoughtful accounts of her own experiences lend a feeling of camaraderie to the book.” —Kirkus Reviews

I went through medical school over 50 years ago. Way back then we were initially taught the correct methods as you have outlined. Then ever afterward we seldom if ever checked our patients with the recommended methods. One thing I think you left out, which can be highly significant. Initial contact with a caregiver must always include measuring BP in both arms several times in the initial encounter. We were also taught this at the beginning and virtually never did it in reality. Measuring / comparing BP: in both arms is the easiest way to detect a patient with an obstruction in one of the arteries supplying each arm. I have an elderly cousin who went 40 years with a undiagnosed significant obstruction in her left subclavian artery that made her left arm BP about 30 mm Hg lower than the right arm BP. She did actually have high blood pressure, but recommendations for treatment varied (seemingly at random, but not actually so) depending on which arm was measured. Decades ago she had had a left carotid endarterectomy to clear out an atherosclerotic obstruction there. She saw what the surgeon had removed, and said it resembled a tube of pure white fat. It wasn't until she got her own BP cuff, tested herself at home, and determined she had a constant marked and durable lower BP in the left arm every time she did both arms in one sitting. She was then referred to a vascular surgeon who agreed with the diagnosis but said she, being 80 years old by then, would not be helped by surgery to clear the obstruction. I have talked to several dozen people with diagnosed HBP, only a single one ever had their caregiver measure both their arms during an initial visit.

A few thoughts...

• It's been many years since I've had a GP doctor who insisted on wearing a white lab coat. The few exceptions have been surgeons, particularly if they were affiliated with a teaching hospital. That doesn't obviate the many other cues present with a visit to see a doctor. Just wanted to note that, in general, the practice of medicine has become more aware of the impact of these cues and attempts to remove them.

• I learned about autonomic hyperreflexia when working at a spinal injury rehab hospital. My takeaway was the degree to which multiple small physical discomforts can collectively contribute to higher blood pressure.

• I've been taking blood pressure reading twice a day (AM & PM) for over 7 years using two different devices, taking the average of three reading per device. (This is also the only two times I check email, so it's time efficient.) Many devices on the market will do this automatically. What I've learned is that the first reading is almost always a throw-away unless I've sat and rested for about 5 minutes before taking a reading. Often, at the doc's office, they take a BP right away, just after I've been driving in traffic, walking up stairs, etc. It's always 10 clicks or more higher than the running average from readings taken at home. I've also had some surprises about what affects my BP in either direction, beyond the obvious ones like stress and physical exertion. Added benefit is that I've become sensitized to the other physiologic signs that tell me if my BP is running high or low. There's a lot more to this, which I write about here: https://remnantsway.substack.com/p/health-and-well-being-part-2-the

• The BP recommendations are a one-size fits all so unless your body composition (and age) matches what science has decided is "normal," it's important to adjust accordingly. For example, I'm 6'5" and a BP of 110/70 has me light headed and at risk for falling. My sweet spot seems to be around 125/85. My cardiologist, who's hip to these variables, agrees.

• I am on medication for BP, which has helped. It runs in the family. The twice daily BP measurements have been a critical factor in working out which medication and dosing.

A suggestion for future article: Body Mass Index (BMI.) A useful metric for populations, but a completely useless metric for individuals. Nonetheless, docs still rely on the BMI to make decisions regarding individual patients. Worse, so do the insurance companies. The Body Roundness Index (BRI) has been around for 13 years and is a better, but still not great, index to follow. The doc offices fail on this measure, too. So much so, I refuse to step on their scales as I'm fully dressed when I do. They subtract a few pounds for clothes. Hell, that's what my shoes alone weigh.